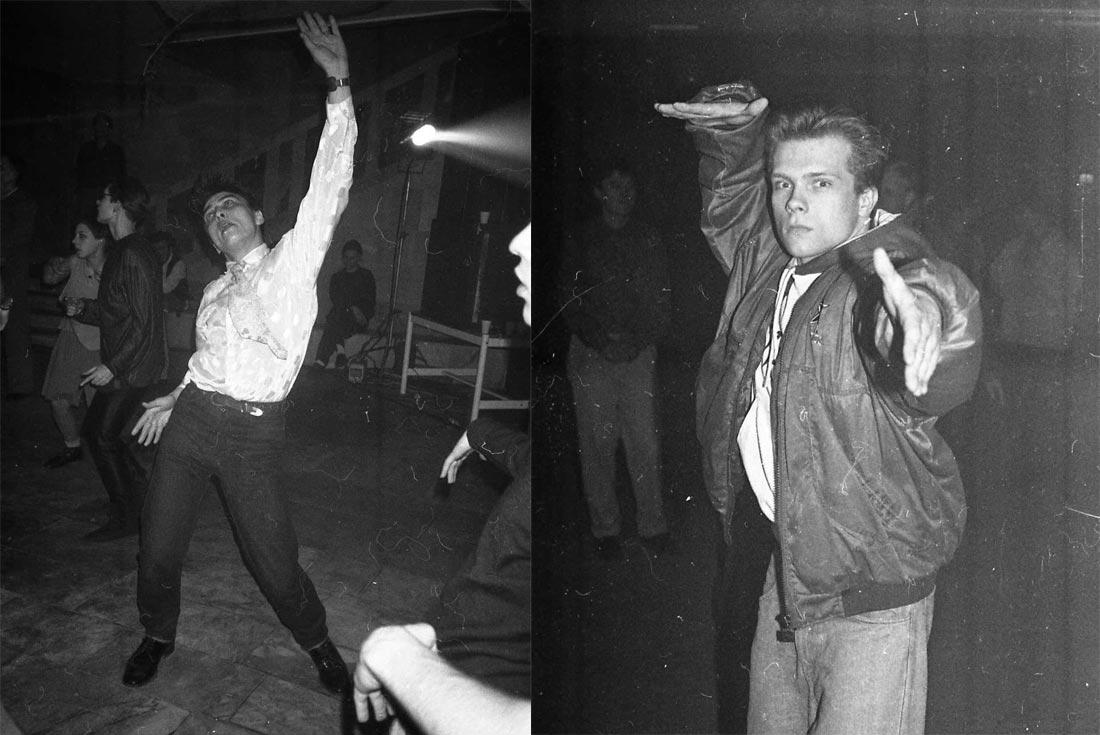

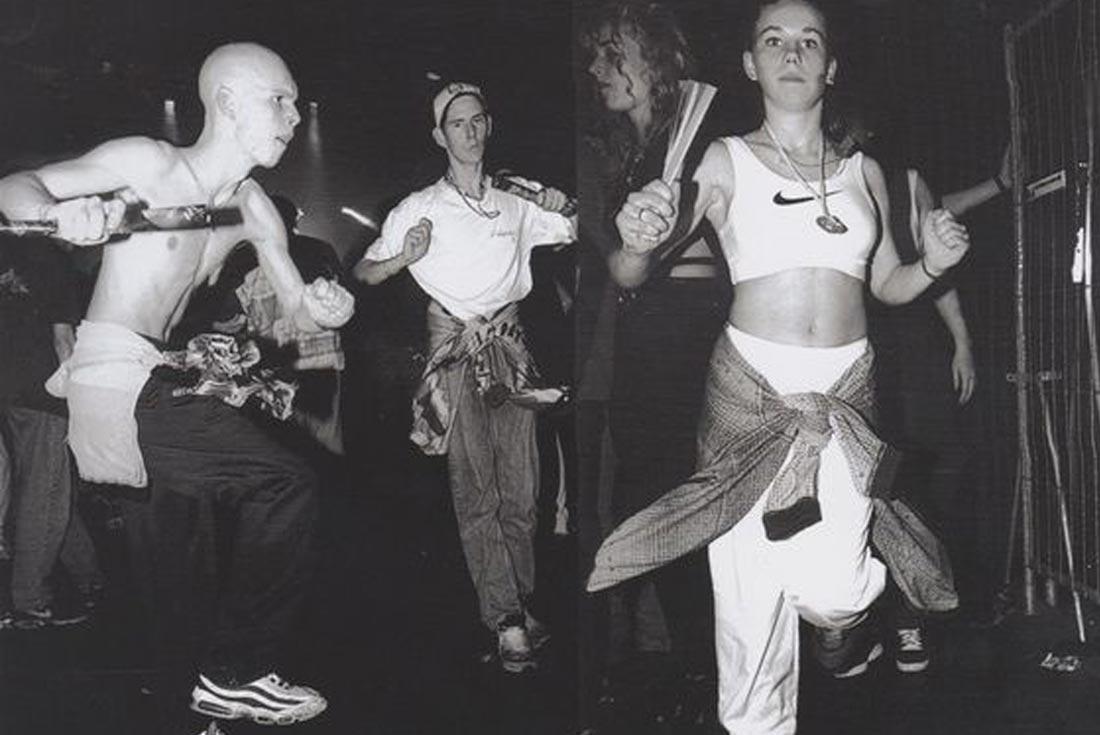

Sneakers That Defined Russia's 1990s Rave Scene

It was December 25, 1991, when Mikhail Gorbachev walked from his post as president of the Soviet Union. The hammer and sickle lowered over the Kremlin for the last time, and Boris Yeltsin took his place in the newly independent Russian state.

Noise reverberated from behind the iron curtain.

Kids from across Moscow and Saint Petersburg took control of abandoned buildings, plugging their DIY raves into the surge of musical influence coming from the West. Clubs like Tunnel, Slaughterhouse and Ptych articulated a new artistic freedom, and offered a place to navigate the existential traumas springing from Soviet dissolution. The floodgates to the West opened, leading to the spillover of imitation adidas, authentic Air Max, and US terrace culture into Russia's local rave scene.

Here are the sneakers that helped forge the new Russian identity.