Parts of a Whole: Crafting Culture in the New Balance 2010

If the isn’t on your radar yet, it might be time to fine-tune your frequency. Blending the hallowed proportions of the 990 series with the turn-of-the-millennium maximalism of the NB1000, it channels the complexity and layering of the hyper-tech running era into a refined lifestyle package. In the engine room you’ve got dual-density ABZORB cushioning in the heel, a mid-foot Stability Web, and plush SBS gel pods for all-day comfort. A nubuck and mesh upper, suede and leather overlays, and metallic silver hits nod to New Balance’s revered running pedigree.

As New Balance’s Senior Creative Design Manager Sam Pearce puts it, ‘Our intention was always to design something new, tell a different story, and not just add another bring-back to the NB lineup… The 2010 isn’t trying to be nostalgic, it’s more reflective. It looks back only so it can leap forward – with intent, clarity, and unmistakable NB DNA.’

That same ethos of remix and reinvention powers Parts of a Whole, a project spotlighting the pioneers shaping Australia’s relentless creative pulse. Shot across Melbourne and Sydney, the series profiles key figures whose work stitches together community, creativity, and culture – each with the same precision and personality that define the 2010 itself.

Part of a whole – and unmistakably singular.

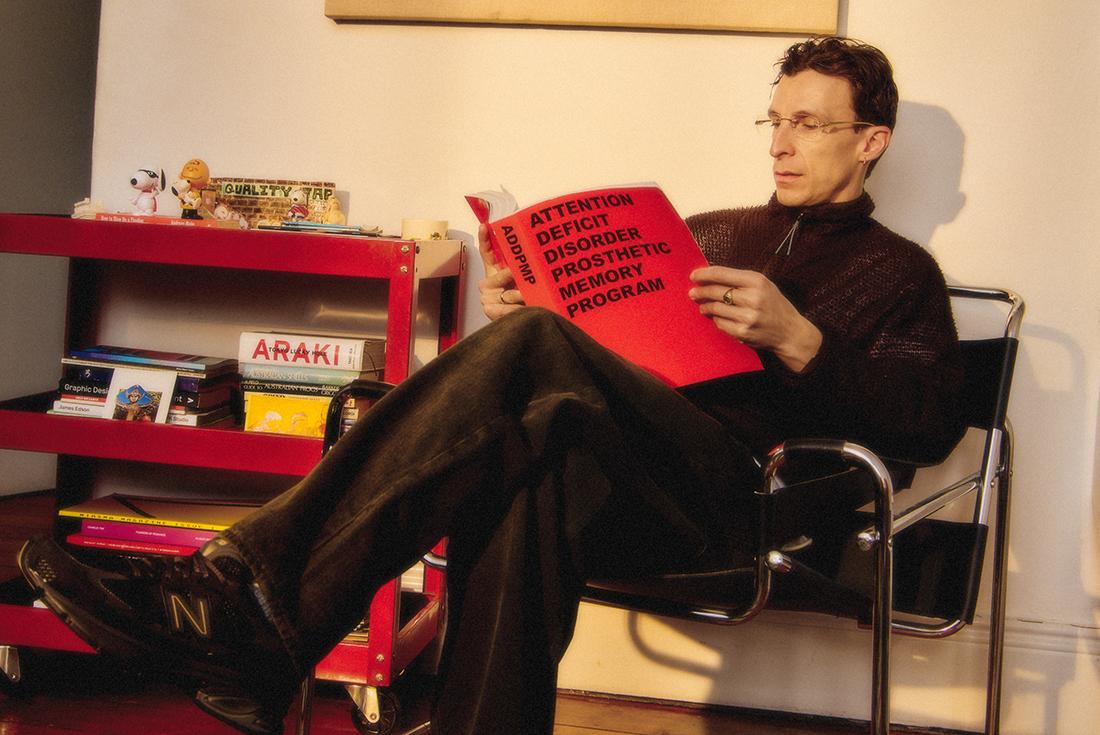

Jesse Hoole – Graphic Designer & Founder of Furies Run Club

Jesse Hoole is a graphic designer whose fingerprints are all over Australia’s underground creative scene. Known for blending the grit of punk and skate culture with clean, purposeful design, Jesse’s work moves effortlessly between gallery walls, gig posters, and the backstreets of Melbourne. Beyond the studio, he’s the founder of , a movement-driven community that challenges the stale norms of running culture with raw energy and inclusive spirit.

Let’s start with Furies – what sparked the idea for the run club, and how have you seen the community evolve since launch?

Furies was born from the collision of two worlds. My love for running often felt hidden – overshadowed by my immersion in design, art, and music. As that passion grew, so did my urge to bridge the gap – to create something that reflected both my identity and a community I knew existed out there.

Running culture around me felt functional but uninspired, with little room for the creativity and individuality that drove the rest of my life. I wanted a space where like-minded runners could find belonging, and where non-runners could discover movement on their own terms. Today, Furies is a diverse crew – from first-timers chasing connection through movement to seasoned runners who, like me, refuse to box in their passions. It’s where running isn’t just a sport, but an extension of who we are.

The visual identity of Furies is raw and unfiltered. How has your background in punk, hardcore, and skate culture shaped the way you design and lead?

Those scenes taught me the power of raw self-expression, DIY values, and supporting others without losing your own voice. That mindset guides everything I create. The most powerful way to share those values is simply by living them.

Your portfolio spans zines, tee graphics, posters, and more. What’s your process when translating a mood or movement into something visual?

It’s an intuitive process, guided by feeling rather than strict rules. Each medium has its own way of connecting with people, but the constant is authenticity – letting my influences shine through without diluting them.

In an increasingly digital design world, what does craftsmanship mean to you – and how do you keep things feeling hands-on?

Craftsmanship means making work that’s authentic, respecting what came before, and letting my personality seep in. I use digital tools, but I pull inspiration from beyond the screen – conversations, digging through old books, deep research. Even collecting references can feel like its own form of craft.

‘Wild in the Streets’ is a powerful phrase – what does it mean to you, and how do you see it in your work and the culture Furies champions?

Originally, it was a rebellious punk anthem about teenage disillusionment and defiance. For me, it’s evolved into a call for freedom – a rallying cry for Furies. It’s equal parts fun and ferocious, pushing back against running’s stale norms and redefining what the sport can be.

The New Balance 2010 draws from archival models but reimagines them for the present. What role does nostalgia play in your creative practice?

A lot of my work connects past and present, reinterpreting history for today. Nostalgia is the emotional spark – whether I’m channelling the feel of a bygone era or reconstructing the visuals and attitudes of another time.

What do you think your work says about how people want to move, express, and belong in 2025?

People want real self-expression, intentional movement, and communities built on shared values. Nothing performative, nothing obligatory – just raw, unapologetic truth.

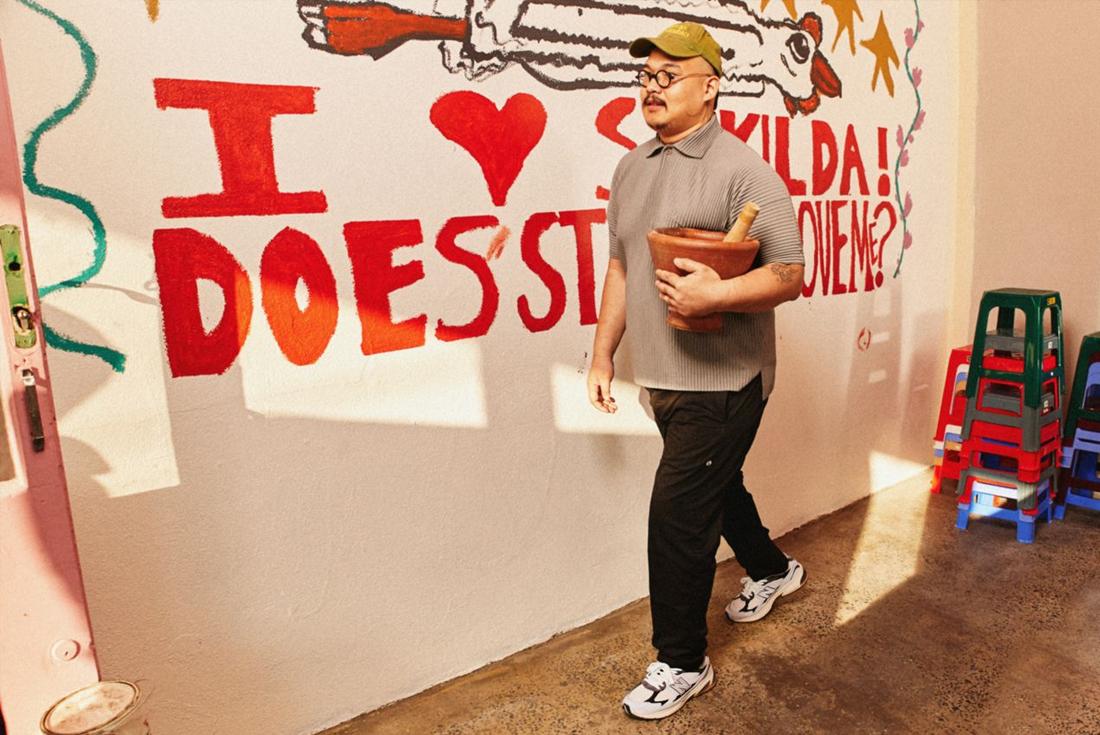

Narit Kimsat – Chef-Owner, Yang Thai

Narit Kimsat brings the city’s flavours to the table. A chef with a résumé stacked with some of Melbourne’s most acclaimed kitchens, Narit has traded fine-dining formality for the smoke, spice, and soul of his own charcoal chicken venture, Yang Thai. What started as a run of pop-ups with a cult-like following is now evolving into a permanent St Kilda fixture, blending Bangkok street-food energy with the easy nostalgia of suburban chicken shops. For Narit, food isn’t just about feeding people – it’s about igniting connections, one juicy, charcoal-grilled bird at a time.

Your pop-ups have built a serious cult following. What have you learned about community from that grassroots momentum?

I was honestly surprised by the turnout across the three pop-ups I’ve done. More than anything, I learned empathy and patience. I realised that if the product is accessible enough, people from all walks of life will come and enjoy it. At the end of the day, I just want to feed people. I don’t want my places to feel like you need to be in a certain financial position to eat there.

You’ve worked in some of Melbourne’s hottest kitchens. What drew you to charcoal chicken, and how did Yang Thai become your next evolution?

There are three things I’ve always wanted to do: a charcoal chicken shop, a noodle shop, and a bain-marie curry place. I went with the chicken shop first because chicken is such an easy, nostalgic thing to explain to people. It doesn’t matter what culture or background you’re from – everyone knows charcoal chicken. City or suburbs, it’s a universal language.

While I was at my last job, I told myself, 'Whatever I do next, I want to be able to explain it simply'. I’d worked in some incredible restaurants, but if an Uber driver asked me what I’d done that night, it was impossible to explain. Now, if they ask, I can just say: I own a charcoal chicken shop.

Then I asked myself: 'What’s the problem with most charcoal chicken?' Usually it’s dry, the flavour is just salt and pepper, and there’s no freshness on the menu. It’s also rarely cooked to order, which is a hard thing to do. That’s when I decided to go with Thai food – juicy chicken, bright salads – but still keep the chips and gravy for nostalgia.

Thai flavours and street-style cooking are at the heart of what you serve, from the use of charcoal grills to punchy marinades. How does your personal history shape what you serve, and what tools or techniques do you always come back to?

I grew up in Bangkok and had a really rough childhood. Recently, I’ve been making an effort to go back once a year – to replace those bad memories with better ones. No matter how tough life was back then, food was always what drew me back. It’s what made me fall in love with the city again.

What I’ve always loved is the spontaneous availability of food there. You wake up – it doesn’t matter what time – and there’s always something to eat. Looking around, I started to wonder why so many of these places were so successful. And I realised: most of them only do one thing, but they do it really, really well. You don’t go to McDonald’s and ask for a pizza.

For me, going back to Bangkok isn’t about chasing new techniques – it’s about observing how food is served, how it’s presented, and the flavour profiles that work. That ties into something my friends and I are always talking about: authenticity. I used to chase it, even judge people on it – whatever the cuisine might be. But that mindset puts you in a pressure cooker. Food here will never be exactly the same as it is in Thailand – the chillies are different, the herbs taste different, the climate is different, and the clientele is different.

So now I’m asking a different question: 'What does authenticity mean to St Kilda? Or to Brunswick?' That’s where my focus is now.

You’re about to open a permanent Yang Thai. How are you thinking about the space, the energy, and what you want people to feel when they walk through the door?

I chose St Kilda because I spend a lot of time there over summer – there’s just so much life. It’s such an iconic suburb, with so many landmarks: The Espy, Luna Park, the pier, The Palace, the Botanic Gardens.

The shop itself is pretty small, so when people come in, I want them to feel like they’re part of the space. We’ll do that thing where we take people’s photos and stick them on the wall – I’ve always loved takeaway spots that do that, like Lamb on Brunswick Street. Hopefully, we’ll get some famous faces too. Xzibit’s playing in St Kilda soon, so maybe he’ll drop by.

I want people to see us cooking, and I want it to feel inviting and fun. A lot of the fit-out is being built by friends I worked with on the pop-up spaces. Another mate, who’s shown work at the NGV, is painting a mural – I told him to do whatever he wanted. If the place ever goes bankrupt, we’ll carve it right out of the wall.

The main colour is pastel pink, which reminds me of Thailand’s Old Town.

Beyond the flames and flavour, where do you look for inspiration outside the kitchen?

Professional wrestling. I’ve always been drawn to the way storylines are built and promoted. In wrestling, there’s a thing called a ‘pop’ – that huge reaction from the crowd – and I think about that same concept when I’m cooking. How can I create a big pop?

I watch a lot of wrestling. It’s an incredibly successful business that’s been around for nearly 70 years, and I’m always thinking about that consistency – performing at the highest level, week in, week out. Monday Night Raw and Friday Night SmackDown have been running every week for decades. They travel the world, perform constantly, and deliver some of the best storytelling of all time.

There’s training, practice, and improvisation. You have to be able to improvise well – because if you can’t, it just looks bad. Wrestlers think through every possible scenario, so they can react instantly when something unexpected happens. There’s a lot to learn from that mindset.

Like the New Balance 2010, your work blends old and new – traditional cooking methods with a modern service style and strong local following. How do you think about connecting with community in a way that feels natural?

When we locked in St Kilda, we took a good look at the neighbourhood. There’s a big Irish community here, so I thought, how can I show them some appreciation? We started stocking Irish soft drinks – a small thing, but it’s a nod to them. There’s also a big backpacker crowd, and their shared passion is pretty clear: football. Once we get our liquor licence, we’ll be showing Premier League games after hours, with a menu that’s easy to serve on those nights so people can just kick back. It reminds me of Thailand – people sitting back with a bowl of congee, watching the football.

There’s also a fitness group that meets every Sunday in Elwood Park, so I invited them to drop by after their sessions and offered them a discount. Down the street there’s a ballroom group I’m starting to connect with as well.

For me, it’s about finding genuine ways to engage with the people around us – not just selling food, but being part of what’s happening locally. I want to make St Kilda feel exciting again. I want people to come and hang out, eat some chicken, have some drinks. I want to be part of their lives.

What does being ‘part of the whole’ mean to you – especially as someone shaping what Melbourne tastes like in 2025?

When you try to be part of something by changing yourself to fit in, you actually create distance – you push yourself further away. But when you lean into being yourself, that’s when you really connect. People are drawn to that authenticity.

I’ve spent a lot of my life trying to be someone or something else, but the truth is, I just have to be Narit. When you show up as yourself, you get invited into more spaces and opportunities than you ever would by pretending.